How Black People Created Every Music Genre in America

America’s love for black culture, but not black people has erased African Americans' role in pioneering American music

March 2021Black people created nearly every major music genre in America, yet black people are underrepresented in industry leadership and awards. It’s been this way since the beginning of the music industry. At the core of this phenomenon is a paradox: America’s admiration for black culture has always coincided with its blatant disdain for black people. Millions of black Americans have to navigate a society that shamelessly sees so much value in their creations, yet so little value in their wellbeing. And nowhere is this unsettling truth more evident than in the history of American music.

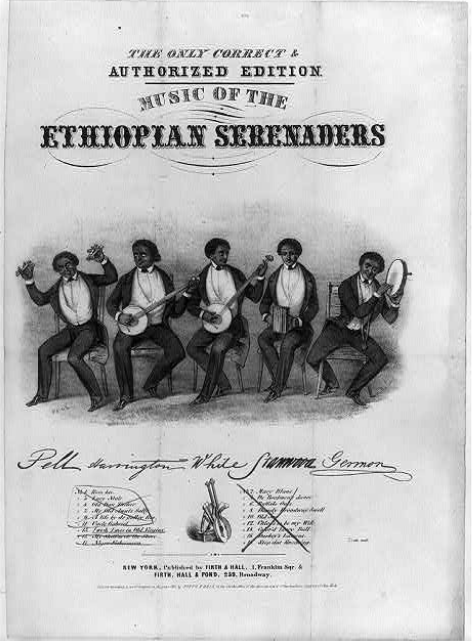

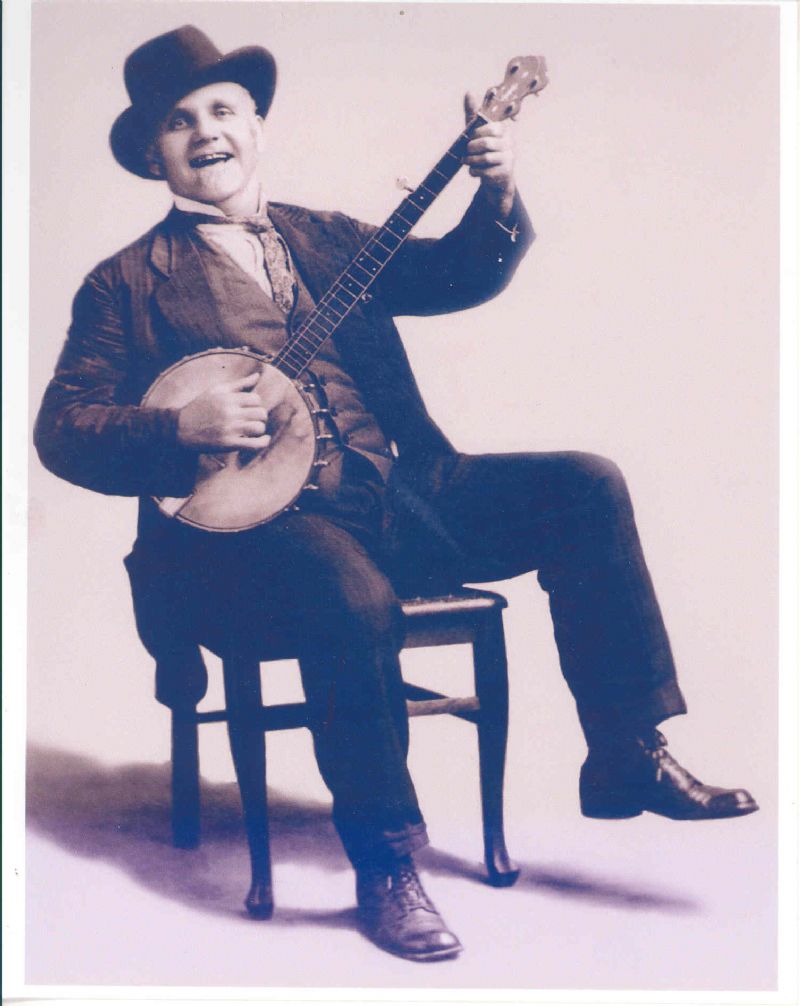

Countless scenarios from music history demonstrate how dissociating black talent from black people abets systemic racism. The banjo, for instance, is the foundation of folk and country music. White musicians learned to play the African instrument from slaves. They then used what the slaves taught them to perform “coon songs'' and minstrel shows that mocked and belittled black people. In the 1920s, some of the best black musicians were able to play jazz at Harlem’s Cotton Club, one of New York City’s most famous nightclubs. At the same time only white people were allowed inside the club as patrons. In the 1950s, doo-wop became so popular in New York City that young Italian New Yorkers created their own doo-wop groups in their neighbborhoods. Black people were not allowed in these neighborhoods, lest they be beaten or chased out by the same groups of white youth that sang covers of black doo-wop songs on the corners. And some of the greatest R&B, rock 'n' roll, and soul musicians played to sold-out venues across the Jim Crow South. As concertgoers danced and sang, ropes separated the black ones from the white ones. Not to mention that some of these musicians weren’t even allowed to enter these venues through the main doors, and upon exiting, sometimes hurried home in fear for their lives.

The story of American music, past and present, is littered with these contradictory circumstances. These days, despite a strong black presence in music, black people are underrepresented in music industry leadership. Black people make up 13 percent of artists and musicians in the industry, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. But black people in the industry argue that the higher up in the industry one goes, the less representation there is. When black people do make it into executive roles it is often in departments overseeing “urban” programs or covering the genres of rap, hip-hop and R&B, they argue.

Fans and professionals alike point out a blatant disrespect shown toward black artists, whose sounds and images propell the industry. Every year, for instance, critics call out the Grammy Awards for its lack of black nominees and winners. In fact, in the program’s 62-year history, less than a quarter of awards for non-genre-specific categories like Album of the Year or Best New Artist have gone to black people. White men top the list of most Grammy wins overall, as well as in categories like Best Rap Album and Best Jazz Instrumental Album. Fans are consistently outraged by Grammy snubs and upsets of widely-celebrated black songs and albums to less-popular or less-critically acclaimed white ones.

Yet black people are either directly or heavily responsible for the creation of almost every major music genre in America, including those currently dominated by white artists and executives, such as country, rock, and electronic dance music (EDM). To demonstrate this I cross-referenced the top 10 songs from the Billboard top singles charts from 1941 to 2020 with genre data from Spotify and Last.fm to come up with a list of the most popular music genres in America. Research into the origins of these genres (outlined in the interactive diagram below) reveals that most of them indeed derive from black people.

I put the results in the interactive diagram below. Genres created by black people or heavily inspired by black people are highlighted. Clicking on the dots reveals more information about the history of the genre and the role black people played in its development. But I also dive more into some of these categories below.

Family Tree of American Music

The research shows that nearly all American-made music genres come from black gospel and the blues. The blues, which is a combination of early black spirituals, plantation songs, and folk music, is a very flexible genre. The blues’s song structure, chord progression, scales, and bar formation are very easy to build on. Thus a multitude of genres, including jazz, country, soul, rock and R&B, sprang from the blues. Despite black people creating these sounds, racist power structures and systemic inequalities deemed the original work in these areas “race music” (read: “niche”) until white artists co-opted them and made them “mainstream.” Indeed, white artists took the genres and ran with them, sometimes never looking back. In some cases white people monopolized the commercialization of these sounds so much that they quickly became their mainstream voices and faces in Hollywood, radio and television. Today rock is ruled by all-white bands. Some of the biggest country acts like the Dixie Chicks and Lady Antebellum proudly named themselves after eras in which Southern white people owned black ones, only recently deciding it looked racist. And techno/EDM has become the go-to music for European raves and their predominantly white celebrity DJs. Similarly, these days one might be hard-pressed to find even a handful of black people swing dancing at the local meetup for jazz enthusiasts, even though it started as a black dance for black music.

Black people aren’t always seen as valuable, but their creations somehow are. As a result, black people are systematically erased and excluded from musical genres they helped create. As their art gets monetized and taken mainstream, they, the people, are at the same time being systematically bullied, killed or disadvantaged. It’s a pattern seen over and over again throughout American history.

The story of one of America’s first pop music genres is also a story of racial inequality. In the opening number to the 1998 Broadway musical “Ragtime,” three groups— a group of white Americans, a group of black Americans, and a group of newly arrived immigrants—take turns singing about the turn of the century and the days of “ragtime.” In the 1890s ragtime was America’s most popular music genre—Black pianists created it as a way to imitate brass and string bands on the piano, emphasizing syncopated riffs and melody. As depicted in the musical, the music was wildly popular with all Americans. As the three groups take turns singing, the white group boasts how in the ragtime days “there were gazebos, and there were no negroes!” But then the group of black people immediately take to the stage, reminding the white group (and the audience) that in fact they, “negroes,” created ragtime.

Ragtime was one of the first music genres created by black Americans and appropriated by white Americans in power. Like the musical depicts, white people placed a value on black culture that they refused to extend to black people, and profited tremendously. Despite black pianists creating the genre, Ben Harney, a white man, was the first to publish a ragtime song. The mainstream popularity paved the way for jazz, which would have a similar trajectory.

Some call that stealing. Yet others say, ultimately, all forms of music are just reimaginings of things that existed before. The way writer and critic Stanley Crouch put it:

“In order to avoid the kind of simple-minded stuff that people engage in today that has nothing to do with the asthenic process, in which they talk about: ‘This white man stole this from that black person. This black person stole this from that white person.’ All artists who are serious steal. So if you're a serious artist and you don't steal, you need to be in another business.” (“Walk on By, The Story of Popular Song,” 2001)

However, this and similar takes downplay or completely ignore the role of racism and racial power imbalances. Everyone in music borrows and “steals,” but who has power, privilege and access to excel and profit on the work? There is also the gross truth that when black culture is loved more than black people, the “borrowing” and “stealing” of black work without uplifting or crediting those who created it only aids in their oppression.

That’s the story of jazz.

Jazz is the indirect result of overt racism. In New Orleans in the 1800s a lot of different cultures lived side-by-side. French, Creole, former slaves, free people, Latinx people and Carribean people shared the city. Many black musicians who were descendents of African and Carribean slaves played blues, typically using brass instruments like the trumpet. Black Creole people were often mixed-race descendants of European colonists and lived in a higher social class than other black people in Louisiana. Black Creole musicians were classically trained. But Jim Crow segregation essentially forced them into the same social class as every other black person in Louisiana. That’s when classically trained Creole musicians mixed with non-Creole blues musicians. The Creole musicians started filling the blues’s slow spaces with improv. Soon the blues musicians started improvising riffs and melodies as well. They called it jazz.

Jazz, a highly improvised and syncopated band music, was a hit in New Orleans and began spreading around the country. Musicians like Jelly Roll Morton started composing jazz songs using the piano and other classical instruments. As the sound became more and more groovy black people started creating various dances to go along with the music. By the 1910s the dances caught the attention of white youth who fell in love with them and the whole jazz vibe. Social gatherings that were once dominated by classical dances like the foxtrot and the waltz became looser as white people began demanding jazz bands perform.

By the 1920s white jazz bands had sprung up across America to meet demand. Many of the white musicians had to learn jazz techniques from black ones. Jazz became so saturated with white artists, though, that some had even claimed to have invented it. Infamously, jazz artist Nick LaRocca not only claimed that he invented jazz, but that it was “a white man’s music”—it had to be.

“Our music is strictly a white man's music. We patterned our earlier efforts after military marches, which we heard at park concerts in New Orleans in our youth. Many writers have attributed this rhythym that we introduced as something coming from the African jungles, and crediting the Negro race with it. My contention is that the Negroes learned to play this rhythm and music from the whites.” (Nick LaRocca, 1936)

LaRocca’s claims were so absurd it essentially ended his career. People knew he was not being truthful, though, racial inequalities would still allow white musicians to innovate and dominate the genre, especially through record deals and Hollywood contracts. Even though black people pioneered the genre, white men like George Gershwin, Paul Whiteman, and Benny Goodman are credited for taking jazz into the mainstream, possibly because they were socially able to.

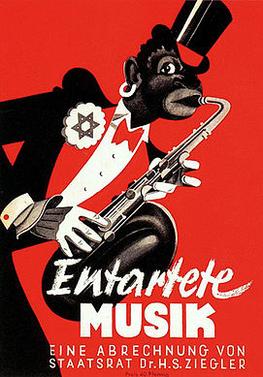

Jazz became so popular with white audiences that white people had to make compromises on prevailing ideologies toward race and segregation to enjoy it. Before he was a household name, Benny Goodman, who grew up listening to black clarinetists, led his own mixed-race jazz band. When he first had a chance to go on tour across America, he took only white band members, fearing middle Americans wouldn’t want to see a mixed-raced band. That tour was credited with introducing jazz to America. In the 1920s and 1930s the Cotton Club in New York City was a mob-owned jazz club in Harlem. Black jazz greats like Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington played to large crowds at the club. However, the club was only open to white people. Even in Germany, swing was such a huge hit with German youth that Nazi officials started a campaign to remind Germans that jazz was was just “jungle music” created by black people and Jewish people (who were often the writers and producers of jazz songs). That couldn’t stop the German kids from listening and dancing to it. As a compromise the Nazis simply changed the lyrics to jazz songs and composed their own to reflect pro-Nazi propaganda, allowing the Germans to keep listening to it. Just like with ragtime, it seemed white people loved consuming black music, especially when they got to repress black people at the same time.

A cringey scene from the 1932 film “The Big Broadcast” depicts exactly what this looks like. It features a young Bing Crosby scatting to jazz while a black man shines his shoes with rhythmic riffs. In those days black people were typically deferred to working class service jobs. On screen they were usually depicted in these roles, subservient to white people. What makes the clip hard to enjoy is how a valuable product is used to elevate the appeal and status of white people, while concurrently degrading the black people who created that very product.

Jazz music is still an international treasure. Yet black people remain disadvantaged in the field. Black jazz musicians still complain about the lack of black representation in industry leadership, tokenism and pay inequalities. Even in the very niche community of jazz dance, black history is largely erased from these spaces. Even though black people created the Charleston, Jitterbug and Lindy Hop, these days professional and amateur swing enthusiasts alike are overwhelmingly white. This is evident among entrants and winners of the country's top swing competitions, and the membership of local amateur swing clubs. As one swing dancer recently wrote: “Say it: we have gentrified black genius.”

Country used to be one of the most diverse music genres in America. Before the 1920s, “country” simply referred to all music that came from the South, especially folk music. This meant that black, white, hispanic and Native American people were creating their own versions of “country.” For black people, that was essentially the blues, a culmination of black spirituals and work songs. For many white people it was spirituals sung in Appalachia with European instruments like the fiddle and harmonica. These sounds would often overlap and inspire one another, though African-Americans would make one of the biggest and long-lasting contributions to the genre.

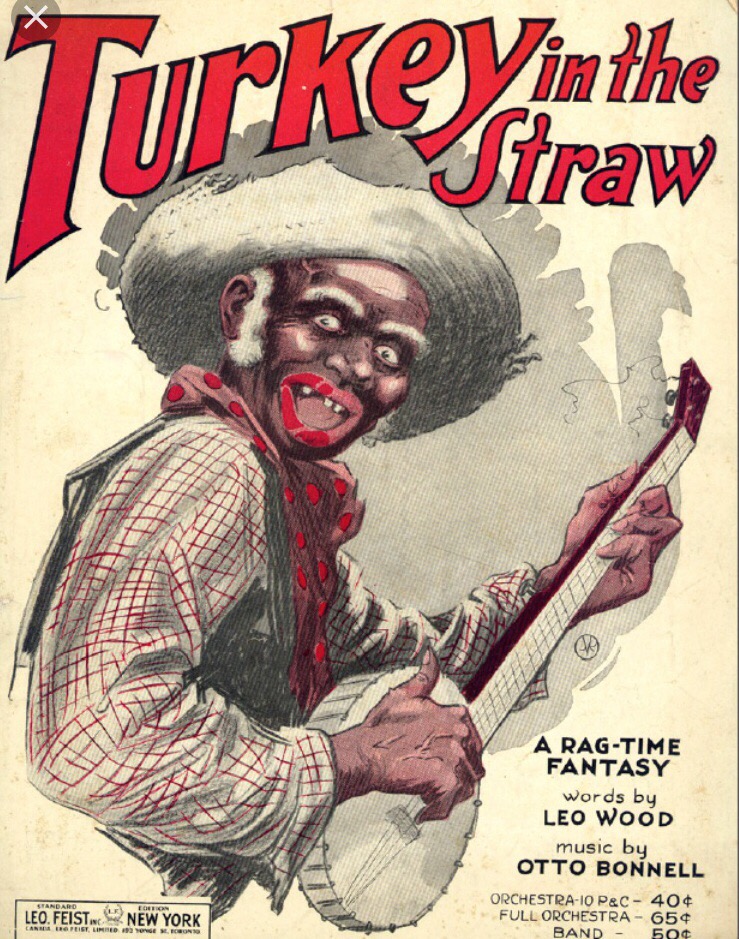

The banjo was, and still is, quintessential to American folk and country. The instrument is an African instrument brought to the U.S. by enslaved black people. The slaves were typically forced to entertain guests at white events, and did so by combining the banjo with other European string instruments. Eventually white people were asking their slaves to teach them how to play it. Soon the banjo became the core instrument of Southern string bands and the primary sound in country and folk.

By the 1920s country music became more commercialized, and despite the fact that many different people were making “country music,” the commercialization of it created racial barriers that primarily benefited white people. In the early days of the recording and radio industries, white country music was branded as “hillbilly music” and black country music was branded as “the blues.” But they were, and remain, essentially the same thing, only sung by different types of people evoking different ideals. Radio exposed country artists from around the country to one another, allowing them to share and adopt techniques. Suddenly white artists could hear how black artists made country music and vice versa. However, white artists were able to take the concepts they learned to the mainstream, bringing them to record labels, radio stations and Hollywood movies.

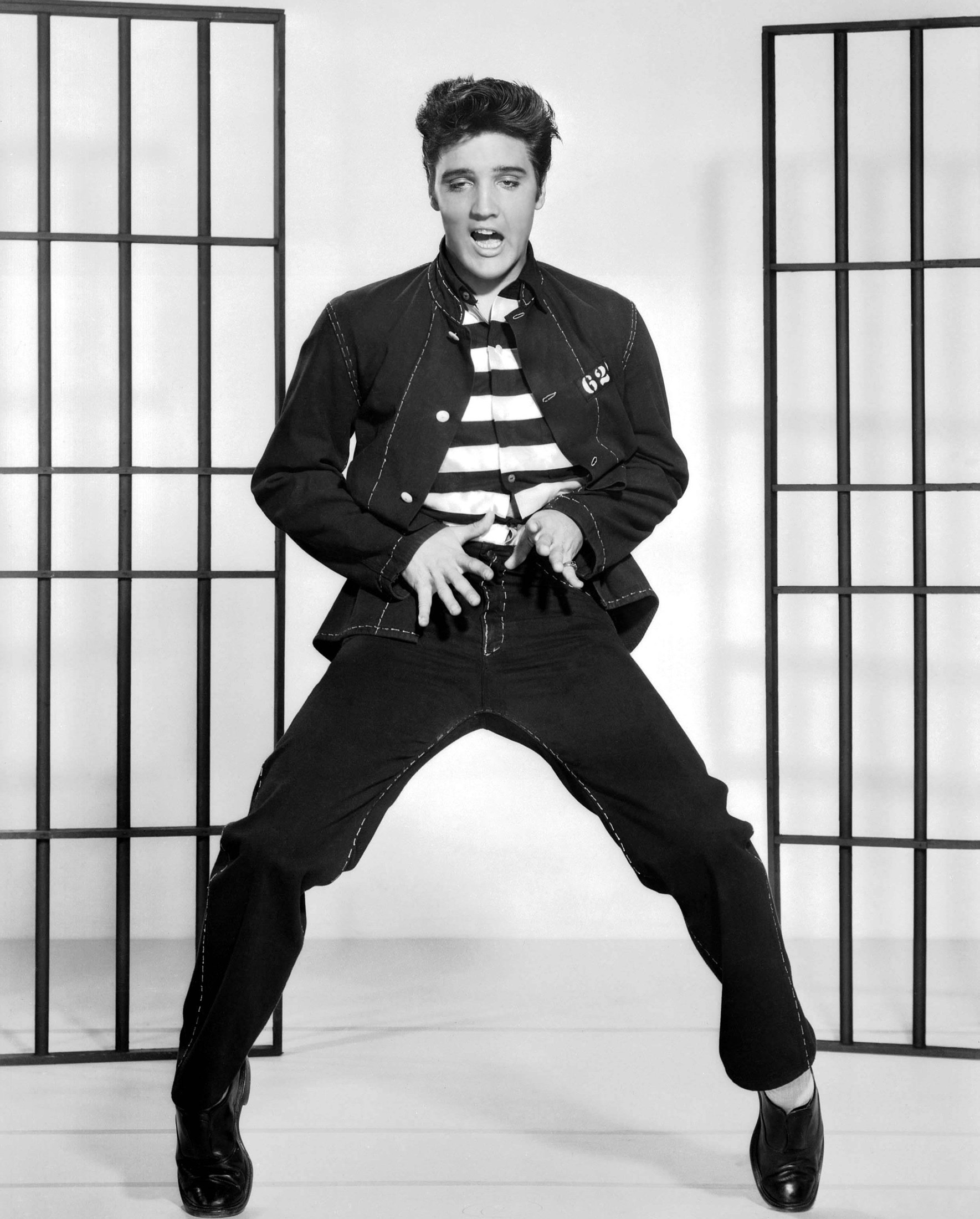

The greatest country artists had black people to thank for their success. Despite white artists’ dominance on the radio waves and in records, many of the great, early, pioneering country singers were famously inspired by or taught by black musicians. Hank Willaims was mentored by Rufus Payne, Bob Wills learned music by listening to black workers, Carl Perkins learned guitar from a black sharecropper named Uncle John (John Westbrook), and Elvis Presley grew up listening to radio stations that targeted black communities. Each of them boasted of the influence African Americans played in their learning their craft.

Such black influence on country music was unrelenting. By the 1940s blues and so-called “race music” (which radio stations later re-branded Rhythm & Blues to simply describe music made by and for black people), became so popular among young, white listeners, that radio and record producers concocted ways to bring those sounds to white audiences sans the black people. The first country songs to top the Billboard charts, Frankie Laine’s “Mule Train,” Tex Wiliam’s “Smoke! Smoke! Smoke!” and Al Dexter’s “Pistol Packin' Mama,” blatantly borrow from black gospel and jazz. Laine adopted black styles so much that listeners often just assumed he was a black man. Williams’s “Smoke! Smoke! Smoke!” is a western swing song, a genre derived from jazz. Dexter’s “Pistol Packin’ Mama” is just a re-written version of “Boil Them Cabbage Down,” a folk song thought to have originated with slaves. In addition to topping the pop charts it landed on the R&B charts in 1943.

Over time country evolved to become even whiter, extending the imaginary gap between it and the blues. A back-to-basics traditionalists movement in the industry starting in the 1980s reconnected country music with its folky, Southern, Appalachian working-class roots. This solidified its image as the unofficial sound of Southern white America, and its “heritage.”

But the irony remains palpable. Today country artists freely incorporate hip-hop and rap into their songs, while black country artists face tremendous pushback within the industry. Among the top Billboard songs I analyzed for this project, several of the country songs on the list, past and present, actually incorporate sounds traditionally associated with black communities. Sam Hunt’s 2017 chart-topping “Body Like A Back Road,' for instance,' sounds like it is describing, rather, objectifying, a black woman—or maybe it’s using imagery associated with black women (braids, curves, “from the Southside”) and terms created by black people to describe themselves, to objectify a non-black woman. Nevertheless Hunt and his team openly discuss their attempts to create “crossover” country music, typically latching on to catchy hip-hop elements. In one recent interview Hunt embraces being known for blending hip-hop and black sounds into his country songs. In the same interview Luke Laird, the songwriter for Hunt’s “Hard to Forget,” also shared how he was inspired by hip-hop and rap when writing the song. “I'm a big Kayne West fan, so I was like if Kanye came across a bin of country records I wonder what he would do with something like that,” Laird said. That’s a stark contrast to the experiences black artists have trying to break into or “crossover” to the country music industry. Singer Lil Nas X opted to re-mix his viral country hit “Old Town Road” with country star Billy Ray Cyrus, after some country radio stations refused to play it, and Billboard removed it from the country charts. Meanwhile when country singer Morgan Wallen was recorded using the n-word, Mickey Guyton, a black female country singer, spoke out about her experiences in the country industry, saying “the hate runs deep.” Guyton has also stated that some of her country songs end up “automatically being [declared] too pop” or not country enough.

Racial discrepancies form the basis of rock, too. In music history, there are generally two types of rock: Rock 'n' roll and rock music. Both are rooted in attempts to make black music marketable to white audiences, though. Rock 'n' roll, the 1950s dance music craze and older brother to what we call rock music, was simply watered down R&B. Producers just repackaged it to sell to white people. Rock music, which evolved out of the rock ‘n’ roll, is essentially the blues, sped up. In fact, pick any classic rock song, slow it down and it sounds a lot like a typical blues song.

Before rock ‘n’ roll was rock ‘n’ roll it was just rhythm and blues. Specifically, it was a danceable version of R&B created by black pianists in the South. Artists like Fats Domino played the piano in a way that was simplified, yet aggressive and rousing. They’d hit the keys or strum guitar strings hard, over and over again, creating high-energy tunes. They coupled the heavy sounds with suggestive lyrics, sometimes using the words “rocking” and “rolling” to describe passionate entanglements. During the Great Migration, black artists brought this style to the North, where it appealed to young listeners, particularly white ones.

In the 1940s, radio waves were usually segregated, with stations devoted to white music and stations devoted to black music. Despite that, by the 1950s producers noticed that white teenagers were still listening to black music via jukeboxes and records. Teenage baby boomers had noticeable spending power and strange, unique tastes. There was a clear demand to be met, and corporate America wanted in. More White radio DJs started playing the music and that’s when one DJ, Alan Freed, supposedly popularized the term “rock 'n' roll.”

But, whatever it was called, white parents didn’t want their children listening to black, innuendo-laced music. If record and radio producers wanted to make rock 'n' roll go mainstream and grab teens’ attention, they had to “clean up” its image. Record producers like Sam Phillips sought out marketable white singers who sounded black. “If I could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel, I could make a billion dollars," Phillips is reported to have said. He found one, by the name of Elvis Presley. Presley, a talented, but amateur country singer at the time, was playing around in Phillips’s recording studio, casually covering the song “That’s Alright (Mama)” by black singer Arthur Crudup. Phillips released the recording, marketing it as “rockabilly,” a mix of rock 'n' roll and hillbilly music (which is what country music was called at the time).

Singers like Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis and Carl Perkins made huge careers as the first rock 'n' roll stars, but they were typically singing covers of songs that had been performed by black people for decades prior. Even they were too risque for parents, however. This prompted the recording industry to sanitize rock 'n' roll even more. They took black rock 'n' roll songs and gave them to more “palatable” singers like Pat Boone. The prim and proper Boone covered songs like Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti,” and Fats Domino’s “Ain't That a Shame.” On the bright side, the white-washed versions made white teens curious about the original versions of the songs, increasing visibility for the original black artists. This made young listeners open up to other black genres like Doo-wop and Motown soul.

Despite white kids’ interests in black music, producers pushed the suburbanization and commercialization or rock ‘n’ roll as far as they could. A slew of young, white bubblegum singers like Fabian and Bobby Rydell copied the rock ‘n’ roll sound, but were branded as parent-friendly. Hollywood films were made featuring rock 'n' roll and white stars, including Elvis. It even went international, becoming a hit in the United Kingdom, which would ironically put some of the soul back into the genre.

The British Invasion and the birth of Rock

In the 1960s British rock bands like The Beatles, The Animals and the Rolling Stones started out singing covers of black songs, but with European flare. Chuck Berry’s “Roll Over Beethoven,” by the Beatles, Sam Cooke’s “Bring It On Home to Me,” by The Animals, and Willie Dixon’s “Little Red Rooster,” by the Rolling Stones, are just a few examples. Inspired by black blues, R&B and soul, the Brits not only returned the rhythm and beat to mainstream rock 'n' roll, but emphasized it. The sound was called merseybeat and was the beginning of a new era of rock, one that centered around “the band.”

Ironically, this new era of rock, heavily inspired by black artists, would slowly push black artists out. Rock became inundated with white male bands singing sped-up blues and calling it something else. This sound was not as danceable as the rock 'n' roll of the 1950s. It was more contemplative, political and experimental. By the 1970s hard rock made the sound darker and edgier. By this time black artists had been left behind. White male bands (Kiss, Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, AC/DC, Aerosmith etc.) dominated the mainstream rock sound, as white, mostly male, bands do to this day. The difference is that rock bands aren’t simply doing covers of black songs, anymore.

Yet black artists continued innovating in music, creating brand new sounds. While young white men in the 1970s indulged in hard rock, a new sound called funk had taken the black community by storm. In a way, it was black people’s response to the wild popularity of “mainstream” rock. Funk artists dressed similarly to wacky rock acts and held large concerts like the arena rockstars. Some even headlined music festivals. The competition between rock and funk fans would give birth to a whole new family of black-made music that, like many genres before them, would ironically become ripe for appropriation.

Cutting-edge music technology in the 1970s offered marginalized groups in America a form of escape from a world that was clearly not made for them (read: hostile toward them). Underground disco clubs and house parties were safe, low-key forms of entertainment for black, Latinx and LGBT people in large cities. When these people weren’t welcome in mainstream spaces, they created their own safe havens. They had a taste for danceable, feel-good music they could call their own. DJs at these venues could use portable music technology to easily play the records that were in demand. In the early days this meant a lot of funk and soul music.

In the clubs, the funk, soul and R&B songs with the heaviest beats were the most popular. They were the songs that emphasized every beat, instead of just the first, or the commonly-used second and fourth beats. This “four-on-the-floor” sound became known as disco. Disco transcended the underground nightclub scene and was eventually everywhere. Record producers used electronic machines to mass-produce disco beats, shoving it straight into the mainstream. Eventually every pop song was a disco song, with a mechanical, repetitive four-on-the-floor beat. It was in nightclubs, on the radio, and in Hollywood movies. It began to overthrow rock music as the country’s top music genres, and pretty soon rock and funk artists found themselves making disco songs, unable to secure record-deals otherwise.

The very society that had pushed marginalized groups into creating their own sounds had now co-opted that sound and embraced it—though not for long. Incensed with the overwhelming popularity of disco, rock fans revolted, creating a “disco sucks!'' movement that effectively killed the genre. People hated disco, partly because it was electronic, repetitive, and threatened rock, and partly because it was embraced by the LGBT community and people of color. It didn’t help that white rock groups like ZZ Top, Eagles, Van Halen and Kiss were now competing with (and losing to) prominent disco acts featuring black women like Gloria Gaynor, Donna Summer, Anita Ward, Sister Sledge, and Diana Ross.

Infamously, in 1979, a Chicago radio DJ hosted a Disco Demolition Night at the Comiskey Park baseball stadium. Tens of thousands of mostly white fans brought disco records to see them get blown up on the field. Following the explosion, the event turned into a riot, with thousands of fans charging the field. Later witnesses noted that many of the records people brought to burn were not just disco records, but black funk, soul and R&B records, and that the event’s undertone felt less about the threat of disco to rock music, and more about the threat of the marginalized people who had created disco to the fans of the largely white-male-dominated genre of rock.

Though rock fans successfully killed disco, the story would repeat. Once disco’s cultural dominance died, its black, Latinx and LBGT creators found themselves back underground. Throughout the late 1970s and 1980s, black and gay underground house parties became their new disco. In Chicago, one popular club was The Warehouse in which resident DJ Frankie Knuckles used music technology to create and play his own, unique concoction of dance music. It became known as House. Meanwhile in Detroit, DJ Juan Atkins mixed the sounds of house, synthpop, funk and soul to create what he called techno. House and techno traveled across the U.S., but became huge in Europe. Europe’s rave and nightlife enthusiasts built on the sound and created many new EDM sub-genres, all while keeping elements of funk, soul and R&B.

Today, EDM, the sound marginalized people created to escape an antagonizing social climate, is once again one of the world’s top musical genres. Yet ironically, black musicians and executives are, again, underrepresented in the genre. According to an Annenberg Inclusion Initiative study, EDM accounted for 5 percent of songs created by racially and ethnically underrepresented artists. Not surprisingly then, the most Grammy-decorated EDM albums are exclusively from white acts like Daft Punk, Skrillex and Lady Gaga, with just a handful of black acts even being nominated.

One EDM genre that appears to still be dominated by black musicians is hip-hop. Like disco, house and techno, hip-hop was formed in the house party scene, particularly in New York City. DJ’s hosting block parties and house parties used turntables to extend the drum breaks in popular funk and disco songs. The DJs realized that people loved these extended breaks and began creating songs with nothing but heavy drum beats. Meanwhile party emcees started talking over the beats in syncopated styles, giving birth to rap.

Like disco and house, hip-hop spawned from marginalization. Whereas black and Latinx youth in the LGBT community had disco and house, hip-hop appealed to a wider array of inner city youth, who had also been marginalized by society. At first rap and hip-hop flaunted disco-heavy sounds (one of the first published rap songs, “Rapper’s Delight,” has a noticeably disco-esque beat), but over time hip-hop grew grittier and grittier, becoming the sound of the streets. By the 1990s rap had become dark, edgy and political. Common themes in gangsta rap were crime, drugs and inner-city living.

In essence, perhaps without intending to, gangsta rappers were rapping about racism, inequality and a broken society. Between the 1940s and 1980s, discriminatory home loan lending and real estate practices allowed white people to flee American cities and buy homes in the Suburbs. Federal programs, like the G.I. Bill that offered subsidized and low-cost mortgages to Americans, infamously favored white people and overlooked black people. The housing industry used “redlining” techniques to isolate black, urban communities and steer white people away from them. Banks and lenders flat out refused to give loans and insurance to black people. Entire suburban covenants and so-called “sundown towns” wouldn’t tolerate black people entering their boundaries, let alone living in them. Even inside the cities, black people entering or moving into white neighborhoods were often met with intense backlash in the form of protest or race riots. White gangs formed to keep black people out of their communities. The first black gangs formed to protect black people from the territorial white gangs. Meanwhile, the scarcity of jobs in the few industrial fields to which black people were relegated began to dwindle. All of this essentially isolated city-dwelling black people inside small urban communities called ghettos, where crime, drugs, joblessness and poverty reigned. These were the communities and conditions gangsta rappers sang about.

The irony is that the children of the people who benefitted from the ghettoization of inner-cities and white flight to the suburbs would turn out to be some of the biggest consumers of rap and hip-hop. The adage goes that more than 70 percent of hip-hop and rap consumers are suburban white kids. Though that specific number is contested, what is clear, from those who flaunt their fanaticism at rap concerts, festivals and on social media nowadays, is that suburban white kids make up a notable chunk of hip-hop consumers. This is a far cry from rap’s earliest days in the 1980s when MTV rarely played black music if at all, earning a reputation for refusing to spotlight black artists in favor of white rock and pop stars. At one point during that era even David Bowie called the network out for its lack of diversity. As hip-hop grew in popularity so did its airtime on the network, exposing the genre to people all over the country.

Many people who grew up listening to hip-hop and rap, are becoming rappers and hip-hop artists themselves, in spite of not being able to personally relate to the marginalization and racial inequities that inspired the genre. A generation of white artists unaffected by the racist housing practices and the ghettoization of American neighborhoods are now chart-topping rappers—Post Malone, Arizona Zervas, G-Eazy, and Macklemore, to name a few. Macklemore even won a Grammy for Best Rap album. Rapper Eminem, who is white, has won the most Grammys for Best Rap Album than any other rapper, winning every time he’s been nominated, except once.

The phenomenon transcends race in America. Among the most recent winners of the Grammys for Best Rap Album are Tyler The Creator, a black rapper who grew up in the third wealthiest black neighborhood in the country, and Drake, who grew up a child actor in Toronto, Canada. A wave of Korean pop bands, known as Kpop bands, have incorporated hip-hop and rap into their genre. Entries and winners for the annual European song competition Eurovision, in which countries across the world compete to create the best song, are filled with hip-hop, punchy rap, and funky EDM sounds. In this globally mainstream form, racial disparity in black America is no longer important. In fact, it’s been erased. Yet the disparities remain, literally still killing black people at alarming rates.

Why does this matter? Some critics argue that race should not be an important factor in discussing music. They argue there is no such thing as black music or white music—that music does not belong to one group. While it would be nice to live in a world where black people could contribute to music and culture without their race needing to be acknowledged, we don’t live in that world. We live in a world where black humanity is constantly being warped and distorted in a way that is contradictory to how black culture is treated. As the world embraces black music and awards the non-black people who make it, systemic inequalities in healthcare, policing, education and practically every other institution continue to kill black people at disproportionate rates. Separating black people from their contributions to society only serves to support these inequalities.

Hip-hop might be headed in the same direction as jazz, swing, country rock ‘n’ roll and techno. It’s becoming mainstream in spite of black suffering. When people say “it doesn’t matter. Music is music,” they are erasing and disregarding the people in favor of the culture. When the black people in black music get erased, so does empathy toward their struggles. Hopefully, by looking at some of the tragic ironies threaded throughout American music history (slave owners leaning to play banjo from slaves, Harlem jazz clubs banning black patrons, rock ‘n’ roll stars playing to segregated concert crowds), we see the dangers in this.