In order to understand Big Brother’s track record with diversity and representation, I created a dataset containing demographic information for every contestant who’s been on the show. I visualized some of the major takeaways of my analysis and presented them in one massive blog post.

Here I lay out the methodology, caveats and thought-process behind the project. I’m also including access to the complete dataset, which can be used for other projects (with full credit and link to this site, please):

The Origins

I got the idea for this project after contestants David Alexander, Ovi Kabir and Kemi Fakunle–all people of color–were evicted together early this season. The image of the trio talking with host Julie Chen-Moonves seemed to resonate with fans, and dug up old conversations about Big Brother and diversity. There were a lot of theories, rumors and suspicions going around about Big Brother casting, representation and trends. I thought why not take a look at the data and see how valid these concerns might be.

The database is actually a spreadsheet/CSV file where each record (row) contains a set of information (fields/columns) about each of the 307 former and current Big Brother contestants. To get started I had to determine what questions I wanted answered and what information I needed in order to answer them. Those questions were:

- What are the general contestant demographics (age, gender, residence, etc.)

- Is there any relationship between minority status and game success?/How far do players of color make it in this game?

- How diverse/mixed are casts each season?

- Have there been any changes in cast diversity over the years?

With these questions I was able to pinpoint the information/fields I needed. The final spreadsheet has almost 50 fields, which can be categorized into three groups:

- Basic info and demographics: This includes name, season number, age, gender, residence, etc.

- Special data: This refers to race, ethnicity and sexuality. These differed from basic demographics because these values were not always at-hand. It took deeper research and more thought into how they should be defined.

- Gameplay tallies: These values represent gameplay success and include number of days in the game, total nominations, total comp wins, and placement.

The Sources

After creating all of these fields/columns in the spreadsheet, the next step was to wrangle the data. I wanted the data to be as accurate and verified as possible, so I used a hierarchical list of sources. First I’d use WayBackMachine to find the original, official CBS webpages for each season for as much information as possible. This worked well for the basic demographic data like names (and their spellings), ages and residences. If the info I needed couldn’t be found there (usually the special data) I tried to see if the information could be found in episodes and clips of the show, usually from the “key reveal” segments. If the episode couldn’t verify the information I’d do an Advanced Google search limited to the year of the season to find articles or forums verifying the information I needed. For the special demographic data (sexuality, race, etc.) if the information wasn’t revealed through the previous methods, I tried to look for first-person sources such as social media posts. In a few cases I reached out to contestants to confirm information. The final tactic was using Wikipedia, which has very well-curated overviews of every season. This would be a last resort, but turned out to be the primary source for the gameplay tallies. Other fields were simply calculated with simple formulas using data from other fields.

Unacceptable sources included hearsay (unverified claims on forums or social media) and fan-sourced wiki sites. I used these for leads, but had to verify the claims with one of the sources above.

The Calculations

Race

Gathering race and ethnicity data was very tricky. Race and ethnicity are social constructs and can mean different things to different people. This made it hard to classify some contestants. This was especially true when it came to the Latinx and hispanic players. Since Latinx/hispanic is an ethnicity and not a race, people who fall into this group can also identify as members of other racial groups. Contestants Josh Martinez, Brendon Villegas and JC Mounduix are all Latinx/hispanic, for instance, but each fall under completely different racial categories. Martinez identifies as Afro-Latino and Cuban, while Mounduix, being of Spanish ancestry would be considered white. Villegas is half-Mexican and white Anglo-American. Then there is the question of identity. Jozea Flores embraces his Puerto Rican and African heritage, while Season 19’s Ramses Soto infamously declared on his casting profile that “I’m not black, I’m Dominican” as a fun fact about himself. Others deemphasize or hide their ethnicity entirely. This makes it difficult to get an indisputable racial breakdown of Big Brother contestants.

The same complexities exist for biracial and multiracial contestants. Olympian Lolo Jones, who came in third place on Celebrity Big Brother 2, is of African and European descent and notably refuses to embrace one over the other, rejecting being referred to as only black or white. Then there are some contestants who identify as both Latinx and biracial.

This made it difficult to determine who went where. Initially, I made judgements based on appearance, and I had no category for biracial contestants. I classified biracial contestants by their non-white heritage and I classified Latinx contestants as Latinx regardless of race. I listed contestants Ramses Soto and Kevin Campbell as black. I listed Steve Arienta, who is of Italian and Polynesian descent, under Pacific Islander. I had always thought Villegas was white. He could certainly pass as white Anglo-American and rarely talked about his Mexican heritage on the show, but I listed him as Latinx/hispanic. Though, I quickly realized that all of this would be very confusing and problematic. Despite physical appearance, personal identification, and social treatment/passing, ultimately players are who they are. Players like Soto or Jones may not identify as black, but both have African heritage. Villegas may be able to pass for white, but he is half-Mexican. Campbell may appear to be African-American, but is half-Japanese.

Because of these complexities I needed to adjust the data structure to accommodate. I decided to create two race and ethnicity fields. In one column I classified Latinx/hispanic contestants as a separate non-white/Anglo category, regardless of racial identity. In the other column I specified each Latinx contestant’s race. Biracial became its own group, containing all biracial contestants, regardless of appearance or the heritage they personally identified with more. Then I added two additional fields to specify both sides of the biracial contestants’ heritage.

With this approach I had six main ethnic groups (Asian/Pacific Islander, biracial, black, Latinx & hispanic, Middle Eastern & Arab, and white). For those whose ethnicities I couldn’t verify, I categorized them as “unknown.” That left a small group of contestants who didn’t fit into any of the above categories. Season 10’s Michelle Costa for instance is Portuguese. Some people assume Portuguese means Latinx or hispanic, but Portugal is not a part of Latin America and Spanish is not its predominate language. Contestant Paul Abrahamian is of Armenian and Lebanese descent. Whether Armenians are “European” or “Middle Eastern,” is often debated and not cut-and-dry. These contestants were grouped as “other,” a non-white-Anglo category.

For the visualization, I separated these eight distinct groups. When it came to Latinx contestants who were also biracial, I categorized them as Latinx (in the database the second race field acknowledges both their Latinx and biracial status with the value “biracial-latinx”). To determine the total percent of players of color I treated all non-white categories, except “unknown, in the “players of color” total, including players classified as “other,” biracial, and Latinx/hispanic. This means that someone like Season 20’s Mounduix, who is of Spanish/European ancestry, would be counted in the non-white tally. That means that in this database and project “white” specifically refers to “white, Anglo-American” contestants, which doesn’t include any hispanic player.

Verifying the contestants’ ethnicities was a challenge. Fan-sourced message boards and wikis gave clues and leads, but I ultimately confirmed each contestant of color’s ethnicity with the official CBS web pages for each season or video clips of key reveal and “Meet the Family” segments. Additionally, I mined social media for terms like “@ContestantName race” or “@contestantName I am a proud” or “@Contestant name latino”, etc. to find tweets of each contestants confirming their ethnicity in some way. When the above failed (this was the case for about three contestants) I reached out to the contestants or their family via email or social media. If this failed, I classified them as unknown. Two contestants on the current season, Analyse Talavera and Jack Matthews, had unconfirmed ethnic backgrounds at the time of publication and thus fell under the unknown category. Once confirmed I will update the database.

LGBT

The verification process for contestants’ sexualities was similar to that of race/ethnicity (first-person confirmation), except I didn’t reach out to any contestant to ask. Confirmation of players’ LGBT status had to come from them, expressed during live feeds, social media posts, broadcasts, interviews etc., or be supported by strong evidence (Season 9’s James Zinkland, for instance, attempted to hide his sexuality while on the show, despite being open about it prior to being on the show. This news spread in the outside world while he was in the house. He is thus grouped under bisexual). So, there should be a verifiable source for anyone listed as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender in this project and database.

The data represents contestants’ LGBT identify at the time of their season’s airing. Players who came out after the show (which have been several) are not listed as LGBT in the database. For this project, “bisexual” referred to players who at any point during the show denoted having past or current affections for both sexes/genders, despite them using the term “bisexual.” Some contestants had discussed their sexuality in hypothetical terms on the show, but unless they had also identified as LGBT or mentioned a history of same-sex relationships or affections I did not classify them as LGBT. Contestants not grouped under LGBT were initially grouped under “straight.” In hindsight I realized that instead of using the term “straight” these contestants should have been categorized as “non-lgbt identified & straight” as not everyone who isn’t LGBT is necessarily “straight.” In the future I may update the dataset, post and visualizations to reflect this.

Calculating Diversity

By “diversity” I mean the amount of variety and balance among subgroups under specific demographic categories like age, race and sexuality. For race, this meant the balance/variety among white Anglo contestants (often overrepresented) and ethnic minority groups (historically underrepresented). For LGBT this meant the balance between members who identified with the LGBT community, openly expressed romantic affections for the same sex/gender or identified as being trans, and those who didn’t. For age, it meant the balance and variety among contestants in their 20s, 30s, 40s and 50+. Teens were not included in age entropy calculations because there has only been one teenaged contestant and the show raised the age restriction from 18 to 21 at some point during the series’s run.

To calculate diversity I used the entropy score formula:

Basically, this formula calculates “evenness” between groups by finding the proportion of the whole that each subgroup represents (pij) and multiplying that proportion by its natural log (ln(pij)), then adding the results of this formula from each group. This is called an entropy score. The entropy score was then compared to the natural log of the total number of groups, which represents the highest possible entropy score, that is, equal proportions across all groups. To make this easier to understand I created a separate column showing the percentage of the highest possible entropy score (ln(6)) that each season’s entropy score represented. For example, the highest entropy score between six groups (ln(6)) is 1.79. Season 18 had an entropy score of 1.51. That is 84 percent of 1.79. In a way that means the season was 84 percent diverse. The bar chart in the blog post depicts the actual entropy score, not the percentage, however.

But the problem with using entropy to measure racial diversity is that the racial categories used are arbitrary chosen. So, as an alternative, I also calculated the ratio of white Anglo contestants to all other ethnicity categories, excluding “unknown.” A ratio of 2:1, for instance, equates to two white people per one non-white person. There is also a field in the data for the opposite ratio (people of color to white people).

All of these calculations were placed in a separate spreadsheet.

Success

“Success” or “progress” can mean anything. For this project I collected gameplay data such as eviction day, total days in the game, placement, comp wins, etc.

The spreadsheet has a field for total days in sequester, which includes the total number of days evicted players spent in sequester before being granted a chance to return to the game in some sort of “comeback” competition. This field is called “comeback sequester.” There is a separate field for total number of days in jury sequester. For seasons with a “jury buyback” style competition that gave sequestered jury members the chance to re-enter the game, the time spent in jury sequester is included in the “comeback sequester” total. Contestants who lost the jury buyback competitions and returned to jury sequester had their time spent in jury sequester prior to the buyback battle added to their “comeback sequester” total. For Season 21 the “comeback sequester” was dubbed “Camp Comeback” and had contestants “sequestered” in the main Big Brother house instead of some secluded location. Evicted members of Camp Comeback had their time in Camp Comeback counted toward their “comeback sequester” total, despite technically being in the house and on the show. These totals were auto-calculated in the spreadsheet by subtracting the day of eviction from the day of their return or comeback competition. Since contestant Victor Arroyo was the only contestant to return to the game three times, I had to manually enter his sequester totals.

Total comp wins only includes Head of Household, Power of Veto wins and special “twist” competitions where houseguests competed against one another for power (i.e. Big Brother Roadkill, Temptation, Hacker, and Hacktivity). It does not include fan votes or food comps.

If I couldn’t verify via Wayback Machine, and also due to speed (some webpages did not tally the results, but instead had them broken up into weekly or daily “recaps”), I used Wikipedia, which for game tallies was most of the time. I used Wikipedia pages for Veto and HOH competition wins, nominations, and eviction days. Therefore, it may be possible that if the Wikipedia pages were incorrect, so would a few of the gameplay tally figures in the database. Though I also tested the data by randomly selecting tallies from the Wikipedia pages and verifying them in other ways such as using the Wayback Machine sites or watching clips from past episodes. So, I am fairly confident in the results.

Lastly, for this project I decided to also calculate player placement as a percentage. Someone who finished in 16th place out of 16 people, for instance, finished in the top 100% of contestants. I then distinguished players who finished in the top 50 percent of co-competitors from those who finished in the bottom 50 percent. There are more accurate and statistical ways to track success, however.

The Visualizations

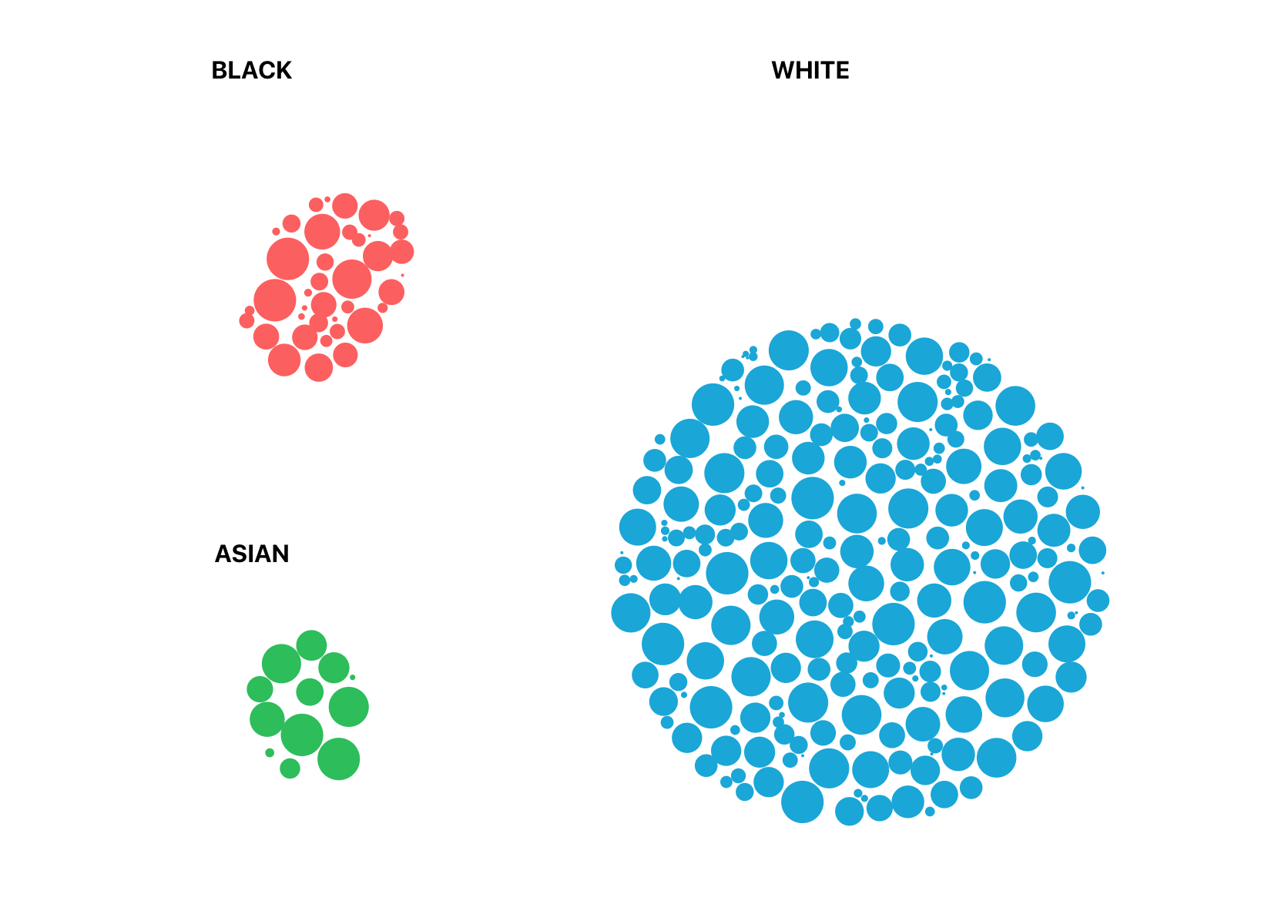

Once I had the data wrangled and analyzed I brainstormed ideas for the graphs I wanted to create. I ended up coming up with a list of three bubble graphs and a bar graph. In the bubble graph each bubble represents one player. The size of each bubble represents how far the player made it in the game. The color represents the player’s value/subgroup for the demographic in question (race, sexuality, age group).

I built one bubble graph and one bar graph using JavaScript and D3, then converted these into templates/object components using the React JavaScript framework. This let me easily reproduce new copies of the original graphs, but with different data and parameters.

Updates

The goal is to update the dataset each year that Big Brother is on the air. If errors are found or points are clarified I will also update the spreadsheet and the visualization, and re-publish the new dataset.

Final Thoughts

Ultimately, this project is a tale about diversity and potential bias in reality TV show casting decisions. When hiring managers are confronted about having a lack of diversity it is not uncommon for some to resort to a handful of ready-made excuses–so much so that these excuses have been written about and criticized by researchers and those who seem to contradict them (qualified people of color). I linked to these pieces in the post, but wanted to re-highlight them here to emphasize the prevalence of this issue and the research and anecdotes that acknowledge it.

What is the pipeline excuse?

- https://www.huffpost.com/entry/tech-pipline-problem_n_57f7f15de4b0b6a43031ee34

- https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2016/07/19/486511816/why-some-diversity-thinkers-arent-buying-the-tech-industrys-excuses

What is the quality excuse?

Debunking the pipeline and quality excuses:

- https://hechingerreport.org/five-things-no-one-will-tell-colleges-dont-hire-faculty-color/

- https://www.vox.com/2016/8/31/12694276/unconscious-bias-hiring

- https://hbr.org/2016/07/we-just-cant-handle-diversity

Anecdotal experiences with the pipeline and quality excuses: